The flashy stuff, as it turns out, is more flash than stuff.

Though this phenomenon persists here in the heartland - an easy road trip from hallowed bourbon country - the geographic inconsistency of this obsession is intriguing.

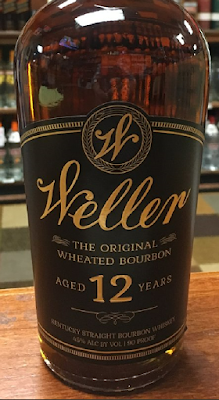

Some real life examples: A rural truck stop always seems to have an eclectic mix of hard-to-find ryes and bourbons (and, for whatever reason, high-end tequilas.) A strip mall liquor store with sketchy lighting in a wine country hamlet had an untouched row of Eagle Rare just last week. And a west coast supermarket recently had Buffalo Trace (for $21!,) Henry McKenna 10 Year, Willet, and even Weller 12 on hand. If those weren't gasp-worthy finds, a Redbreast 21 for the reasonable tariff of $275 was spotted in the wild at a beverage store in the country's most expensive real estate market. Anyone who has ever coveted a special bottle has heard salacious, annoying tales just like this, but they are as confounding for their possibility as they are their lack of fairness.

Why are these whiskies, which create stampedes in some markets, quietly waiting on shelves on the west coast? The simple answer is that they aren't selling there.

When perplexed by market questions, microeconomics has been a reliable place to start in the search for answers. Laws of supply and demand ultimately determine price and availability. These laws exist within markets, some of which know no boundaries (i.e. crude oil,) while others have sharp geographic focus (i.e. real estate.) So, if you happen to be shopping for rare whiskey in Louisville, for example, (arguably the epicenter of bourbon culture,) you are not alone. Every brown-liquor-loving tourist and their brother has already scoured the shelves for what's on your wish list. In other words, demand is high.

Supply, by contrast, is dictated largely by, well, the suppliers. They've been at it for centuries, and know their markets well. Smart Kentuckians have never felt the need to spend a lot or chase to enjoy good bourbon, but there are plenty of romantics in other places willing to pay a premium for the braggadocio of certain labels. So, suppliers push product to where the romantics have fat wallets.

To maximize profits, the nuanced concept of scarcity comes into play. Scarcity - or at least the perception of it - has been a key factor in preserving demand. To that end, distilleries and their wholesale partners don't simply push all their supply to where foolhardy fans are, they spread it around, calibrating it carefully.

Alas, this is as much fallible art as it is fallible science, which is why there's EH Taylor sitting on a shelf a six hour drive from where grown-assed men dream of overpaying for a bottle. Which brings us back to the west coast. California often serves as a trend-setting market. Is the availability of "rare" bourbon there an indication that its time has past? If my past prognostications are any indication, not yet.

Just in case, though, I hope the speculators in the mania sell before a wave of bourbon indifference hits their shores. Or start to actually drink the stuff.

Special thanks to Jerry for the idea on this.